History of the Arabic Bible

The Bible at the Emergence of Islam

At the time of the emergence of Islam there is no evidence of a Bible in Arabic. Christian and Jewish communities used Scriptures in Hebrew, Aramaic, Ethiopic, and Greek in their worship. The earliest surviving Arabic Bible texts date from the 9th Century, but the translations themselves may be older.

The Earliest Translations

The earliest Bible translations are written in Middle Arabic—a combination of classical and colloquial Arabic. Middle Arabic was highly influenced by syntactical and lexical usages of Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac, Coptic, and Greek. These translations were criticized for “mistakes” and “bad Arabic” (especially by al-Jahiz, who died in 868 AD). Arabic was often a second language for the communities who used them.

Notable Christian Translations include:

- Mt. Sinai Arabic Codex 151. Translated by Bishr ibn al-Sirri in Damascus in 867 AD.

- Pethion ibn Ayyub as-Sahhar, a Nestorian Christian, MS Arch. Seld. A67

- The “Elegant Gospels,” probably dating to the 9th Century

- The lectionary of Abdyeshu, a Nestorian bishop.

This lectionary is dated 1299 AD, and was written in Nisibis, now known as Nusaybin, on the border between Syria and Turkey

Significant features:

- The translations were individual books or collections of related books (Torah, Epistles, Gospels, etc.)

- The translations often use language easily understood by Muslims

- Many have what one scholar calls “A Muslim cast” to the language

- Some use rhymed prose (saja’), such as Abdyeshu’s lectionary

- There are a number of Arabic versions of the Diatessaron (the Four Gospels combined in a single narrative)

Jewish Translations

The earliest translations of the Old Testament into Arabic were penned for Arabic-speaking Jews throughout the Arab World. The most significant translation was done by the famous Rabbinic scholar, Sa’adyah ben Yosef al-Fayyumi ha-Ga’on (882-942).

Sa’adyah’s Translation

Sa’adyah wanted a translation that was natural and understandable in Arabic. When he found one did not already exist, he embarked on his work. He called it the Tafsir. This translation became a standard for Arabic-speaking Jews for centuries. It was also used in some of the famous “polyglot” Bibles produced in the early modern period.

What can we learn from ancient translations?

Early Arabic Bibles used the same language, terminology, and style as their Islamic counterparts.

Key Theological Terms

Early translators used the same vocabulary as Muslims for many key terms, these being just a sample:

- The Basmala (bismillah ar-rahman ar-raheem, “In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful”)

- Baptism: sibghat allah

- The People of God: qawm rather than sha’ab

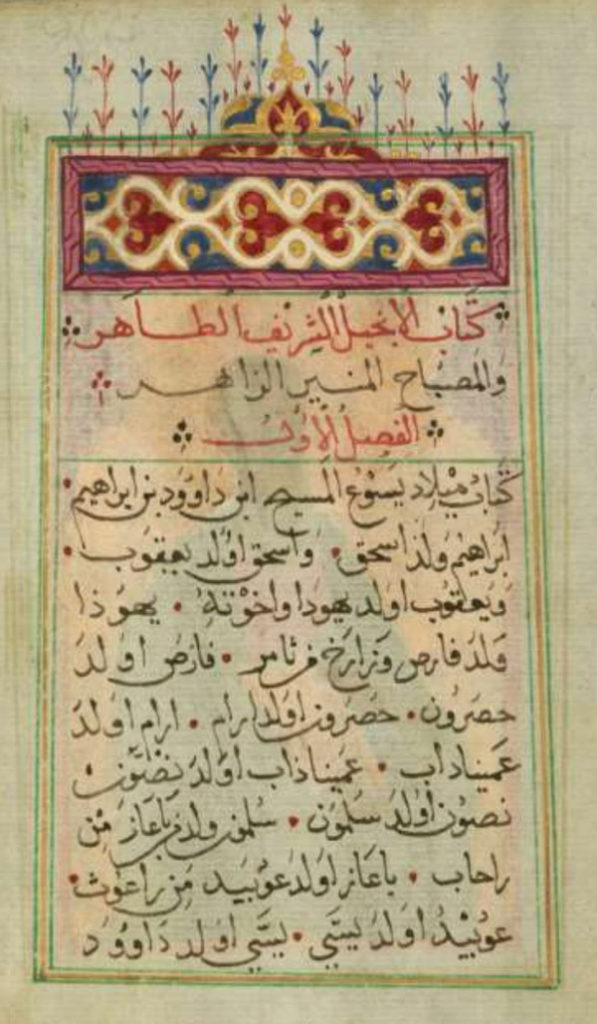

Matthew, 1684:

Note the honorific title on Matthew: “The book of the pure noble Gospel and the brilliant lamp that gives light.”

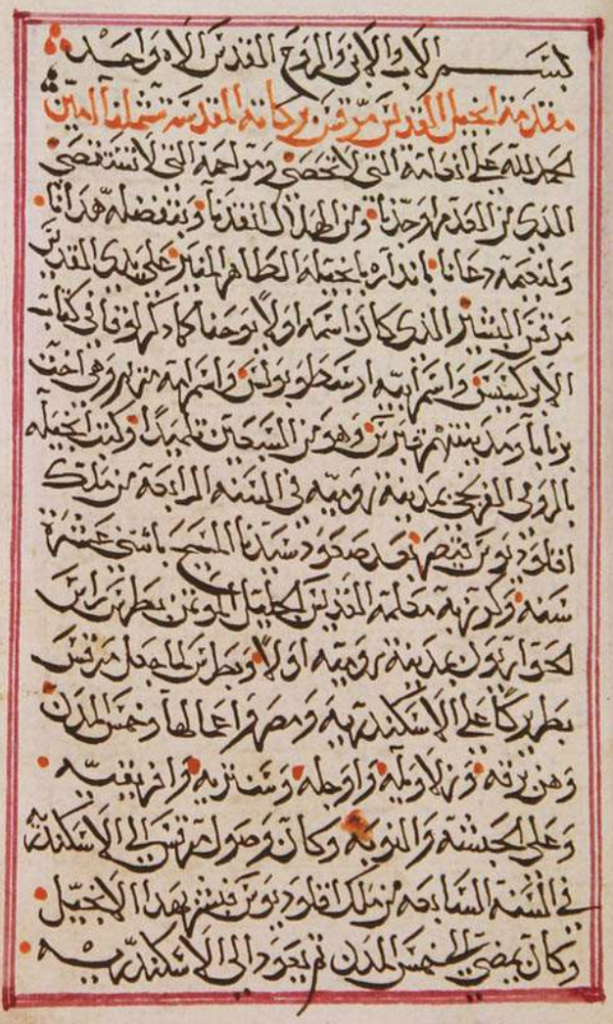

Mark, 1700s:

Note the Trinitarian basmala on Mark, from Matt. 28:19

Approaches to Challenging Texts

Early translators used terminology familiar to Muslim theologians when rendering challenging texts. For example:

- Exodus 3:14 “I AM WHO I AM.” Sa’adyah uses, al-Azaliyy alathi la yazuul (The Eternal One who is without end).

- John 1:1 “And the Word was God.” The Ali Bey translation into Ottoman Turkish (from 1665) uses the expression found among Muslim theologians “bi-dhat allah.”

Divine Names

Early translators used familiar vocabulary to refer to God.

Jews use seven names to refer to God, all of them epithets. When transcribing Scripture, they used a special pen and ink for these seven names. The holiest of these is YHWH.

Most languages do not have seven names for God like Hebrew, so they have to be translated with fewer names. To some extent English does this, since both YHWH and Adonai are translated as “the Lord/LORD.”

All Arabic translations translate Elohim as Allah, and translate Adonai with one or more words meaning “Lord.” Like English, they do not translate YHWH in a third way, but as one of these two. Sa’adyah, one of the most respected figures in Rabbinic Judaism, considered that “Allah” was appropriate to translate YHWH. The Sharif Bible and True Meaning translations both follow the lead of Sa’adyah.

Style

While the earliest Arabic Bibles were criticized for being wooden and difficult to understand, Sa’adyah and Pethion chose a different approach, sticking more closely to qur’anic diction.

The Muslim biographer an-Nadim said of Pethion, “He was the most accurate of all the translators from the point of view of translation, also the best of them for style and diction.”

One scholar speaks of a “Muslim cast” to Pethion’s work and other ancient translations. This means the use of certain phrases and grammar familiar to Muslims.

Intertextuality—Language in Conversation

Intertextuality recognizes that the meaning of a text is partially shaped by its surrounding texts. Julia Kristeva writes, “…every text is constrained by the literary system of which it is a part, and that every text is ultimately dialogical in that it cannot but record the traces of its contentions and doubling of earlier discourses.”

Jews and Christians during the Abbasid period were deeply involved in the intellectual currents and discussions of Arab society of their time. Their Bible translations often chose to communicate using the terms and concepts in common use. These were, as Dr. Sidney Griffith observes, “stock phrases or oft-repeated invocations” that “though perhaps not exclusively Islamic or Qur’anic, are nevertheless thoroughly Muslim in their resonance.”

A Conversation Interrupted

Around the ninth century, Arab Christians began to turn from the East to the West. Griffith notes “…from the Ottoman period onward, Christian projects to translate the Bible into Arabic increasingly relied on the support and active participation of Western Christians.” The Crusades were a major factor in this retreat from traditional Islamic-Arabic terminology. Shirley Madany writes, “With the polarization of Christians and Muslims ever since the Crusades 1095-1291, Christian Arabs have developed many terms and expressions which are purely Christian.”

Modern translations typically use terms, phrases, and even grammar from the liturgical languages, Greek and Syriac, reinforcing the perception that Christianity is a foreign religion. The dialectic dissonance builds a wall between Christians and Muslims. Newer translations are often discredited by Muslims because of bad grammar, bad style, foreign words, and inappropriately translated anthropomorphisms.

Lessons from Ancient Translations

Notable ancient translations engaged the culture around them, using standard terminology and styles that were shared with Islam. Later Christians chose to move away from common Arabic terms, creating unnecessary distance and hostility between Muslims and Christians. Our vision for the True Meaning is to reduce that distance. We believe that everyone who is seeking God deserves access to the Bible.